Crop insurance is a vital safety net for farmers, protecting them from financial losses due to poor harvests or declining crop prices. The Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP) in the United States has been instrumental in providing this support, with the USDA offering subsidized crop insurance. In 2022, the program supported about 1.2 million policies, covering 493 million acres, at a cost of $17.3 billion. This included subsidies for premiums, administrative costs, and compensation for insurance companies. From 2000 to 2021, FCIP offered support for 133 unique agricultural commodities, covering an average of 284 million acres annually.

The program has evolved since its inception in the 1930s, with legislative changes and premium subsidies increasing participation. In 2021, the aggregate crop coverage level reached 74%, with insured acreage rising to 444 million acres. While the program benefits farmers, it has also faced scrutiny for the substantial amounts flowing to insurance companies and agents.

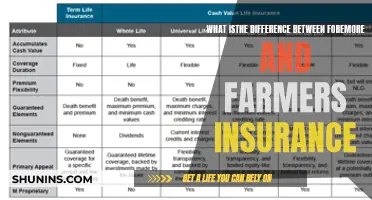

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of farmers benefiting from crop insurance | 460,615 policyholders in 2022 |

| Percentage of total insured liability in 2021 | 74% |

| Average annual participation from 2000 to 2021 | 284 million acres |

| Number of unique agricultural commodities supported from 2000 to 2021 | 133 |

| Average subsidy for high-income participants | $1.2 million |

| Average subsidy for participants with income less than the limit | $7,480 |

| Total cost of the program from 2011 to 2021 | $90 billion |

| Total cost of the program in 2022 | $17.3 billion |

| Projected total cost of the program over the next decade | More than $101 billion |

| Percentage of premium subsidies in the total cost of the program in 2022 | 62% |

| Number of policies supported in 2022 | 1.2 million |

| Total acreage covered in 2022 | 493 million acres |

What You'll Learn

The US Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP)

The program's participation has increased steadily over the years, with insured acreage rising from 206 million acres in 2000 to 444 million acres in 2021. This increase in participation can be attributed to legislative changes, including premium subsidies and the introduction of new insurance products. For example, the introduction of policies for Pasture, Rangeland, and Forage (PRF) coverage contributed significantly to the recent rise in insured acres.

The total cost of maintaining FCIP has also increased with its growing participation. Premium subsidies, which are the largest share of total program costs, totaled $3.11 billion in 2020. In addition, FCIP incurs other costs due to its public-private partnership structure, where private insurance companies, known as Approved Insurance Providers (AIPs), sell and service the insurance policies. In 2020, the cost of program delivery (administrative costs) was $1.68 billion, and $1.36 billion was paid as underwriting gains to AIPs.

The federal crop insurance program helps farmers obtain insurance to protect them when crop prices decline or harvests are affected by natural causes. The USDA partners with private insurers to implement the program, and in 2022, the federal costs were $17.3 billion, with about $12 billion subsidizing premiums and the remainder covering administrative costs and government losses related to the policies.

The program offers subsidized crop insurance to protect farmers against financial losses, with subsidies averaging about 62% of policyholders' premiums. In 2022, the program supported approximately 1.2 million policies, covering 493 million acres, and is projected to cost over $101 billion over the next decade.

Farmers Insurance and the Question of Maintenance Warranty Coverage

You may want to see also

Premium subsidies for farmers

In 2022, the federal crop insurance program supported about 1.2 million policies, covering 493 million acres, at a cost of $17.3 billion to the federal government. Of this, about $12 billion was allocated to subsidizing premiums, making it the largest portion of the program's total cost. The average subsidy from taxpayers was about 60% of the total premium, with farmers contributing the remaining 40%. This arrangement has been in place for decades, with taxpayers heavily subsidizing the Crop Insurance Program.

The absence of an income limit for subsidy eligibility has resulted in substantial subsidies for high-income participants. For instance, in 2015, a participant with an annual gross income (AGI) exceeding $900,000 received an average of $1.2 million in premium subsidies annually, while those with lower AGIs received approximately $7,480. This disparity has led to suggestions for Congress to implement an income cap, reducing subsidies for high-income policyholders, and redirecting savings to other Farm Bill priorities.

The effectiveness of the program has been questioned due to the high cost to taxpayers and the concentration of benefits among a small number of large commodity farms. While the program is intended to provide a safety net for farmers, it has been criticized for disproportionately benefiting private insurance companies and wealthy farmers, with payments reaching a record $11.63 billion in 2022.

Reforms have been proposed to modernize the program, reduce costs, and improve accessibility for small and midsize farms. Suggestions include capping subsidies, eliminating or reducing subsidies for high-income farmers, and restructuring administrative and operating costs. These changes aim to strike a balance between supporting farmers and ensuring efficient use of taxpayer funds.

The Future of Farmers' Livelihoods: AJ Farmers Union Insurance in Billings, MT

You may want to see also

Insurance companies' administrative costs

The Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP) is a public-private partnership between the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and private insurance companies. The USDA subsidizes the premiums that farmers pay for crop insurance, and also pays the insurance companies for their administrative and operating (A&O) expenses. These A&O subsidies are meant to cover the costs of delivering the program, including company salaries, agent commissions, loss claim verification, and regulatory compliance.

In 2022, the federal government paid insurance companies about $3.7 billion to deliver the program, with about $2.2 billion in A&O subsidies. The A&O subsidies are calculated as a percentage of the premiums, which was about 21.5% in 2005. While the A&O percent subsidy has decreased over the years, the total reimbursement to companies has increased due to higher total premiums.

The insurance companies that service crop insurance policies are known as Approved Insurance Providers (AIPs). In the last 10 years, these AIPs received almost $33.3 billion from the federal Crop Insurance Program, with about half of this money coming from taxpayers to cover administrative and operating costs. The actual amount received by each company can vary, as agents get a percentage of the premium of each policy they sell, and the companies can choose to provide additional compensation within statutory boundaries.

The Federal Crop Insurance Program's public-private partnership structure has led to concerns about the high costs for taxpayers. From 2011 to 2021, the total cost of the program was about $90 billion. Critics argue that the program benefits private companies more than farmers, with billions of dollars going to insurance companies and agents. There have been calls for reforms to reduce costs and better serve farmers, such as lowering program delivery payments and restructuring how administrative and operating costs are determined.

Farmers Insurance and Farm Bureau: Understanding the Difference

You may want to see also

Underwriting gains and losses

The risk-sharing arrangement between the government and insurance companies is outlined in the Standard Reinsurance Agreement (SRA). Under the SRA, the government acts as a reinsurer, bearing a portion of the companies' underwriting losses (which occur when indemnities exceed premiums) and, in return, taking a share of the companies' underwriting gains. This arrangement allows the government to help shoulder excessive losses in bad years while receiving underwriting gains from farmer premiums in good years.

The government shares in the risk of loss for two main reasons. Firstly, there is a requirement for universal availability of crop insurance. Companies must sell a policy to any farmer who wants one, regardless of risk. Due to these restrictions against normal underwriting practices, insurers would typically consider this an uninsurable risk. The SRA mitigates this issue by allowing companies to transfer a portion of the risk to the government. Secondly, agriculture is inherently risky, and the potential for large-scale losses may exceed the capacity of the private sector. Natural disasters can impact many individual farms simultaneously, and the resulting correlated or systemic losses could bankrupt a private-sector company.

From 2001 to 2010, the government saw $4 billion in underwriting gains, which were offset by underwriting losses in 2011, 2012, and 2013. The government once again realized underwriting gains in 2015. Over the last 10 years, crop insurance companies and agents received almost $33.3 billion from taxpayers and farmers, with a significant portion coming from underwriting gains.

The federal government's compensation to insurance companies includes subsidies for their administrative and operating (A&O) expenses and their share of underwriting gains. In 2022, the government paid insurance companies about $3.7 billion, including about $2.2 billion in A&O subsidies and about $1.5 billion for their share of underwriting gains. The government's compensation to insurance companies is projected to average $3.8 billion yearly from 2024 through 2033.

Farmers Insurance Military Discounts: Unraveling the Benefits for Service Members

You may want to see also

The impact of climate change

Climate change is making insuring crops more risky, with payouts from the nation's biggest farm support program increasing by $27 billion between 1991 and 2017, according to a Stanford University study. The study found that hot, dry conditions caused by climate change have added billions of dollars to the cost of the federally subsidized insurance program that protects farmers against drops in crop prices and yields. The researchers compared indemnities in each US county to itself under different weather conditions and found that payouts were higher in warm and dry years. With the growing intensity and frequency of heatwaves and other severe weather events, costs are likely to rise even further.

The Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP) insures participating farmers against adverse production or market conditions. The cost of administering the FCIP rises in years with adverse weather events, such as droughts, when insurance claims outpace premiums paid for insurance coverage. As the frequency of adverse weather events changes, so do premiums. Climate change could affect the Federal Government's fiscal exposure from the FCIP as premiums and subsidies adjust to changing growing conditions. Adverse weather could make yields more variable from year to year, causing losses to happen more frequently. Commodity prices could become more variable if adverse weather events affect large proportions of farmland at the same time, also increasing the frequency of crop insurance losses.

The Environmental Working Group (EWG) has also highlighted how crop insurance discourages farmers from adapting to a warming planet. For example, it has been noted that crop insurance has encouraged farmers to plant environmentally damaging crops, year after year, driving erosion across the fertile soils of the Midwest, increasing the use of polluting fertilizers, and unleashing soil carbon. Anne Schechinger, a senior analyst at EWG, has argued that by shielding farmers from risk, crop insurance encourages risk-taking because farmers are playing with "house money". She suggests that Congress should tailor crop insurance to reward greener farming practices, such as encouraging farmers to retire marginal land or use less fertilizer.

In response to the growing impact of climate change, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has efforts underway to encourage agricultural producers to enhance their resilience. The USDA has developed and shared information about climate change with farmers and ranchers and plans to better integrate climate resilience into agency decision-making through annual updates to its climate adaptation and resilience plan. Additionally, some USDA programs may provide indirect incentives for producers to enhance their climate resilience.

Exploring the Unexpected: The Farmers Insurance Museum

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In 2022, the Federal Crop Insurance Program supported about 1.2 million policies.

The Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP) is a US government program that offers agricultural producers financial protection against losses due to adverse events, including drought, excess moisture, damaging freezes, hail, wind, disease, and price fluctuations.

In 2022, the Federal Crop Insurance Program cost the federal government $17.3 billion. The program's cost is projected to total more than $101 billion over the next decade.

The Federal Crop Insurance Program covers a wide range of crops, including barley, corn, cotton, flaxseed, oat, peanut, potato, rice, rye, sorghum, soybean, sugarbeet, sugarcane, sunflower, sweet potato, tobacco, and wheat.

Farmers benefit from the Federal Crop Insurance Program by receiving financial support and protection against losses. The program also helps farmers manage their financial risks and protect their earnings against drastic swings in crop prices.